Pediatric Stone Disease Treatment

There have been remarkable breakthroughs in the past 20 years in the treatment of urinary stones. Prior to this time, the only option for removal of stones was an open operation. Now, open surgery is very rarely performed for stone disease.

If open surgery is proposed for your child's stone disease, ask about less invasive treatments that might be available.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL)

The most cutting-edge treatment for urinary stones is ESWL: breaking urinary stones with shock waves from outside the body. In this form of treatment, x-rays or ultrasound are used to focus shock waves on the stone, breaking it without damaging the body's normal tissues.

Is ESWL Safe?

The safety of ESWL on the developing kidney has not been established beyond a doubt, but it seems from many large studies that this is a safe and effective way to treat pediatric kidney and ureteral stones.

Does My Child Need Anesthesia to Undergo ESWL?

In adults, some forms of ESWL can be given without anesthesia, but most children require at least sedation to keep them calm and still so that the focus on the stone can be maintained. The more powerful forms of ESWL are painful; children require anesthesia for these forms.

Does My Child Need Further Treatment After ESWL?

Most kidney stones in children can be treated with ESWL. Other treatments may be necessary due to:

- Previous failure by ESWL to fragment the stone

- The child's anatomy, or previous reconstructive operations on the urinary tract

- The size of the stone; large stones may best be treated by removing the entire stone, rather than subjecting the kidney to multiple ESWL treatments and the possibility of obstruction due to a "roadblock" of stone fragments in the ureter

Endoscopic approaches

In some situations, endoscopic approaches are most useful in treating urinary stones in children. Endoscopy refers to using telescopes inside the body. The urinary tract has long been approached using "cystoscopes" (bladder scopes), as well as ureteroscopes and nephroscopes (kidney scopes).

Urinary Tract Surgery Using Telescopes

The specialty of "endourology" refers to the use of such telescopes to perform surgery within the urinary tract. The most common application of endourology involves the removal of urinary stones.

- Kidney stones may be approached endoscopically in two ways: through the bladder and ureter (ureteroscopically) or through the skin (percutaneously).

The pediatric ureter is smaller than that of the adult and can be injured by surgical instruments, alt hough the recent introduction of smaller flexible ureteroscopes has made access through the ureter feasible. It is more likely, however, that a percutaneous approach will be used for a large stone.

- The percutaneous removal of kidney stones (percutaneous nephrolithotomy, or PCNL) was developed for the removal of stones in adults and has been used in children without modification, for the most part.

A few groups have tried to "downsize" the instruments to make them more appropriate for children, but these efforts have been sporadic.

Mini-perc technique

Recently, UPMC pediatric urologists have developed a technique referred to as the "mini-perc", which was specifically designed for pediatric PCNL and also has been applied to adults. With the assistance of Cook Urological, they have developed a sheath for pas sage of miniature endoscopes (Circon/ACMI), allowing removal of kidney and ureteral stones through a small puncture.

The technique has been applied to many different stone types in children, who range in size from 11 pounds up to adulthood. In most instances, an interventional radiologist will place a tube into the kidney the day prior to surgery. This percutaneous nephrost omy tube gives us access to the kidney.

Sometimes the specialists will skip this step and obtain access in the operating room. They pass a guide wire into the kidney, and over this wire pass a catheter (tube) that has two passages. This is then used to introduce a second "safety" wire. The catheter is then removed and the sheath is inserted.

Once the sheath is in place, the stone(s) are either removed whole, or fragmented and removed. Stones can be broken using several forms of energy, including laser, ultrasonic, and electrohydraulic. Small rigid and flexible telescopes can be used to see all pa rts of the inside of the kidney and ureter.

Stones and fragments can be removed using miniature graspers and baskets passed through the scopes. UPMC pediatric urologists have used the mini-perc technique for years with success equal to standard forms of percutaneous stone removal. It is important to no te that more than one procedure is often necessary to remove all stone fragments, and that a small nephrostomy tube is left in the kidney until the process is completed.

Surgery for bladder stones

Bladder stones in the United States are most commonly associated with urinary tract reconstruction, either for bladder exstropy or neurogenic bladder. Stones often form in bladders that have been enlarged or "augmented."

Percutaneous techniques are now used routinely to remove such stones, often on an outpatient basis. The use of percutaneous techniques to remove bladder stones results in an average hospital stay of one day, as opposed to approximately five days for open surgery.

Treatment at UPMC

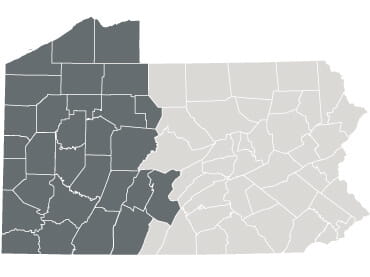

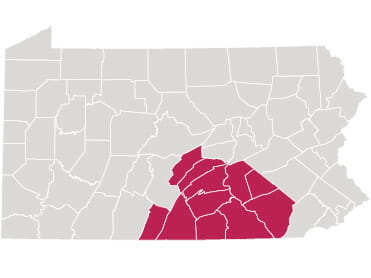

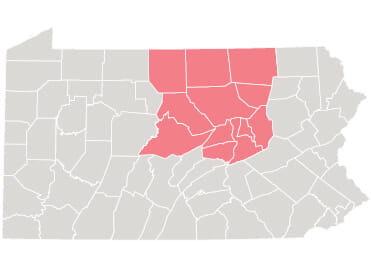

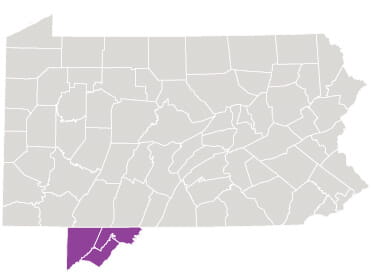

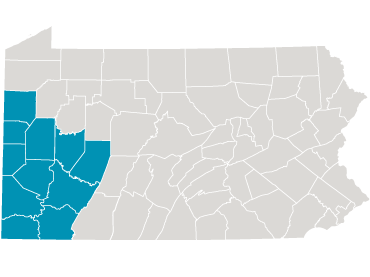

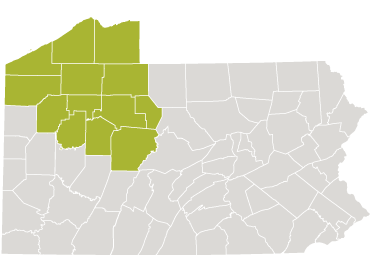

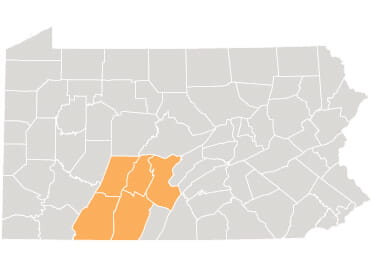

The Department of Pediatric Urology at UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh is a mul tidisciplinary clinic that treats and manages pediatric stones. A team of specialists, including a urologist with specialty training in the management of stone disease, a nephrologist, and a nutrition specialist, create a treatment plan and follow the patient's progress over the long term.

Contact us to schedule an appointment, 412-692-4100.